Keith Badman’s 2004 Beach Boys Definitive Diary is the most detailed chronological concordance currently available for any Beach Boys timeline – but its ‘definitive’ claim is challenged by astute Amazon reviewers:

I picked up this book and started to read the first substantive page, Page 10. The very first paragraph states: “Hawthorne is situated in rural southeastern Alachia County very close to the boundary of Putnam County.” Of course Hawthorne, California is, and always has been, located in the western part of Los Angeles County, near the Los Angeles International Airport. Further, there is no Alachia County nor Putnam County in California. If the book starts out with such a glaring error, is the rest of the book filled with other pieces of misinformation not so easily identified?

and a Comment concurs:

I was all set to buy this, but if they don’t know Hawthorne is in LA county what else is wrong with this book? Is it real??

Maybe it isn’t – maybe none of this is real. ‘Alachia County’ doesn’t even exist, but Alachua County (in Badman’s spelling) does. It’s in Florida.

Beach Boys Corp. have been comparably as inattentive with their own specifics through the ages; but narrative changes are more often agenda-driven shifts rather than errors – and even the latter can be more conveniently reliable than, you know, the facts.

(broadcast in US June 2012, UK Dec 2012, trailer here, don’t buy it here)

31 mins in, the 2012 Beach Boys are in conversation about Good Vibrations:

Al: Brian, where did you get the idea for the theremin?

Brian: Theremin? Uh, Carl.

Mike: Really?!?

Brian: He said ‘why don’t we use a theremin – and a cello’.

Mike: Come on!

Brian: Honest to God.

Mike: Carl Wilson said that?!?

Brian: Yeah, my brother Carl suggested using a theremin and a cello both.

Mike: I never knew that.

Brian: Yeah, absolutely.

Brian Wilson may seem convinced, but he is incorrect – and Mike Love himself is fully aware that it was Van Dyke Parks who suggested the cello for Good Vibrations. How could Mike forget? Why would Mike not correct Brian, instead of feigning surprise?

In another promotional group interview (in Mojo, June 2012),

Brian pipes up to state that it was [Van Dyke] Parks who turned him on to LSD and amphetamines. “We wrote Heroes and Villains on uppers”, he says, adding with delightful ingenuousness that “I’m not sure, but I think The Beatles took psychedelic drugs too”.

Al Jardine instantly disputes Brian’s claim about Parks, adding, in a near-whisper, “I wouldn’t say that”.

“Well, if that’s Brian’s recollection…” interjects Mike Love.

Given that Parks has continued to voice criticism of Love over the years, hidden agendas may be jutting through here.

With all Mike Love’s claims of Good Vibrations co-authorship, he might not want it known that he was also collaborating by proxy with Van Dyke Parks…

‘Brian’s recollection’ became unreliable years ago; Peter Ames Carlin (in Catch A Wave), describes Brian Wilson in the 1980s:

Some observers concluded that he had suffered a stroke or was showing the latter-day side effects of the mountains of cocaine and the rivers of alcohol he had ingested in the 1970s and early 1980s. But when Brian made a surprise appearance at a Beach Boys’ fan convention in the summer of 1990, it didn’t take long for Peter Reum, a longtime fan who happened to work as a therapist in Colorado, to realize something else… Given his professional training, Reum suspected that Brian’s twitching, waxen face, and palsied hands pointed to tardive dyskinesia, a neurological condition that develops in patients whose systems have become saturated with psychotropic medications, like the ones Brian had been taking in quantity ever since Landy had taken over his life in 1983.

Mike Love knows all this (and how could he not?), but his cousin’s flawed memory suits Beach Boys™ when an incorrect answer fits the corporation’s agendas – either hidden, or more bluntly revealed. Ultimately it all becomes what Mike Love wants you to believe; whether he believes any of it himself is mostly irrelevant.

In the Front Row Center ‘documentary’ (and in common with any previous Beach Boys’ approved fictions), Smile is either treated as an aberration, or, like Van Dyke Parks, never existed at all. And, despite the band’s actual 50th Anniversary celebration being November 2011’s multi-format Smile Sessions release, Doin’ It Again‘s chronology fails to mention Smile, leaving a larger data gap than their 25th anniversary revelry. In that, official, cue card-driven version of events,

this is Brian Wilson (c.1987):

and this is Brian Wilson (c.1966):

this is Mike Love:

and there was never any kind of Van Dyke Parks.

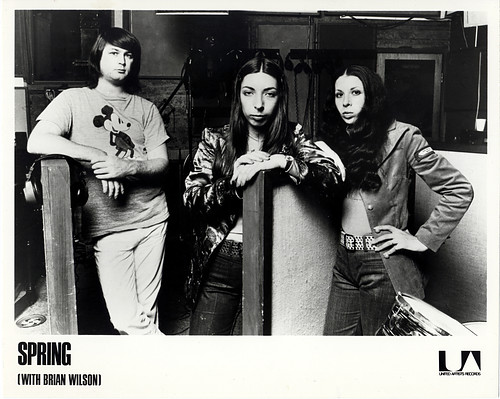

These are Beach Boys:

This, to the filmmakers, is what Smile was about:

(here, in its willfully-ignorant, ignominious, and shamelessly self-celebratory glory)

Maybe Keith Badman is correct: maybe Hawthorne is in Florida; maybe future official histories will reveal that the band’s birthplace was actually Kokomo instead.

Beach Boys history is a tale still in limbo, and it’s not yet apparent how it will all end. But, while not a ‘war’ as such, more a series of ‘preemptive strikes’, history will, as usual, be rewritten by the victors. The 2012 Doin’ It Again ‘revelation’ cited above is just one recent strike in this decades-long campaign of disinformation and willful obfuscation.

With the Beach Boys’ own 50th Anniversary Tour past and gone – and ending with some of the same vague acrimony that has consistently defined the band’s history over the past 4 decades or so – Beach Boys Corp now presents Made In California, a 4CD box set that puts Smile back into the corporate context it briefly escaped from with 2011’s Smile Sessions box set.

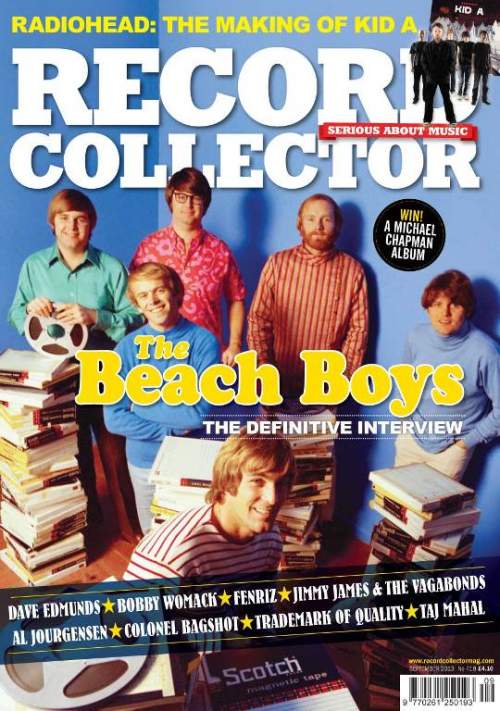

The September 2013 issue of UK mag Record Collector has a ‘definitive interview’:

The Beach Boys are about to release Made In California, a major box set where classics jostle with rare gems. The band talk frankly about their incredible career

and the ‘Editor’s Letter’ describes the piece as ‘a powerful and extensive interview of admirable honesty and integrity‘. It is of course no such thing, being instead a disconnected series of responses to a disconnected series of questions; the entire Q&A reads like a press release (the US Rockcellar Magazine has pretty much the same ‘interview’ online here; the entire thing appears to have been supplied to both publications, as opposed to sourced by either).

Ken Sharp’s questions often seem leading rather than probing:

Mike, your collaborations with Brian were extremely successful. Around ’64, when Brian began writing with Gary Usher and Roger Christian, and later with Tony Asher and Van Dyke Parks, did you ever question why he was “taking it out of the family”, so to speak?

With any foreknowledge of the band’s ignominious history, one need not read Mike’s response further, because he reiterates here his own selective memory about The Beach Boys themselves. Answers offered might as well be written in advance. On cue-cards.

Mike cites, again. The Ballad of Ole Betsy (an utterly obscure and mostly-disposable early album track) as one of the band’s more poignant moments; this song was his own ‘fuck you’ (in June 2012’s Mojo Magazine) to those fan fools that rate

in

![]()

(same 2012 issue of Mojo – The Ballad Of Ole Betsy does not feature. Nor Kokomo.)

Mike’s own constructed belief in his literary worth reappears in conversation with Ken Sharp:

I was the most well-read child in grade school, junior high and high school…I’ve always had a fondness for lyrics, prose and poetry of various kinds…

Etc. Etc. Etc.

If one were utterly unaware of the historical role Mike Love had and has within The Beach Boys, this interview could maybe pass for ‘honesty and integrity’ – but, even in its honesty, Beach Boys Corp still tries to keep Smile buried in the sand. And Mike’s role in Smile‘s non-release in 1967 is – again – dismissed (by Mike himself) as myth:

I think there’s a lot of brilliant music on SMiLE. Brian, thankfully, has gone on record as saying “Mike had nothing to do with the shelving of SMiLE”, though people have been saying I didn’t want it to come out. I had nothing to do with that. Brian freaked out on LSD and shelved it.

This new paradigm reached its apogee in his own appreciative essay for the 2011 Smile Sessions book, where, in the absence of any comment from the album’s lyricist, Mike Love says:

I have seen where [Brian] said that I didn’t like the SMiLE album. Others have said that it didn’t come out because I was against it. First of all, it was not my decision nor was I asked or involved in the decision to shelve the album.

Note the caution in his non-answer…however, while

the instrumental parts of the SMiLE sessions, are some of the most amazing recordings…the lyrics on some things were not my cup of tea, and the term I came up with to describe some of those lyrics was “acid illiteration”

(Mike seems as keen on the Celinian ellipsis as I am…and what was in the space taken by those three dots that his lawyers maybe removed?)

But where Mike’s responses in Record Collector/Rock Cellar show a tempered loquaciousness, Brian’s own answers are mostly brief, saying little of substance, and nothing new. And Mike seems keen to quote Brian where the latter has ‘gone on record’ removing Mike from the Smile equation; Brian Wilson has said elsewhere – and recently – that Mike did have more than a little to do with the shelving of Smile: A BBC Radio 4 promotional interview for its 2011 release has Brian saying, about Mike in ’67:

He was disgusted with it, he said “I’m DISGUSTED with this”

Would this recollection also be ‘on record’? Or does it need to be in print before it can be used as a legitimate ‘proof’? What is considered on or off the record might only stand up to scrutiny in a court of law. Mike’s lawyers have taken various family (and band) members there before (stuff about one his more ridiculous lawsuits is here – and as hilarious a read as it might be, there is a pertinence to Mike’s claims that will be revisited in a later post).

And while Smile (and Van Dyke Parks) is discussed in passing, no one in this interview mentions, even in passing, the release of The Smile Sessions in November 2011. Two historical box set releases in 2 years?!? The first receiving a Grammy for ‘Best Historical Album’ in 2013?!?

That ‘major box set’ wasn’t anywhere near as worthy (or as useful) as Made In California will be to a touring ‘Beach Boys’, which will persist on into 2014 – without Brian Wilson, Al Jardine or David Marks. Mike Love and Bruce Johnston’s geriatric karaoke conceit will be filling fairgrounds and farm dances across the US for years to come off the back of this new collection .

But if The Smile Sessions had remained The Beach Boys’ final, defining legacy statement, upon its release in 2011, where would Mike’s Moopets go then…?

Speculation. Idle thoughts. Back to this timeline.

Record Collector is correct, however, in that the current band narrative is ‘incredible’. It’s occasionally unbelievable, often contradictory, often lacks any real psychological insight on the part of participants, critics, readers…and with The Beach Boys’ history as kind of common knowledge amongst rock music’s middle-aged cognoscenti, there is, far as I am aware, only one person who feels The Ballad Of Ole Betsy usurps Surf’s Up as The Beach Boys’ greatest recorded lyric.

And it’s this perpetual ‘world turned upside down’ that persists, to deliberately and consciously undermine Brian Wilson’s proper place in the history of popular musics of the 20th century.

If one wished to attempt a journey into the life and the mind of Brian Wilson, the concerted efforts of Mike Love (as CEO of Beach Boys Corp.) to further this disinformational obfuscation means that any such investigation can only ever be speculative. Brian doesn’t remember – but Mike does. He thus knows what has to remain unsaid, undiscovered, unexplored – and Mike Love will use whatever opportunity comes his way, in order to rewrite a story which might otherwise show him to have little real function in the actual history of why The Beach Boys were ‘important’ in pop music’s own story.

Brian Wilson’s own thoughts, motives and recollections from 1966 and ’67 are now mostly lost; any inaccurate utterance he might make this century – ‘on record’ – that supports The Brand (rather than The Facts) thus becomes part of the fragile and contradictory narrative maintained by the custodians of The Beach Boys’ trademark. The Record Collector interview offers no insight into The Beach Boys’ history that cannot be read anywhere else that Mike Love has been allowed to air his New Revisionism (try here and here, for starters and for laughs).

Therefore, regardless of accuracy (or inaccuracy), in the timeline that follows, an attempt is made to contextualise why Mike feels his history needs rewriting and reiterating ad infinitum. Any dates cited below use the Definitive Diary purely as a framework for a loosely-chronological series of postulations and speculations.

Looking beyond ‘what if Smile had been released’, there seem to have been many points in this post-Smile period where one small event could have completely altered Brian Wilson’s own timeline – and his 21st century destiny might have been rather more than as a mascot – and a trophy – for a 21st century Beach Boys™.

With their own history in perpetual rewrite, there are thus no obvious sources for The Beach Boys saga that can ever really be ‘definitive’. Least not on my bookshelf.

Maybe you know better. Comments are open. Please cite sources.

1967.

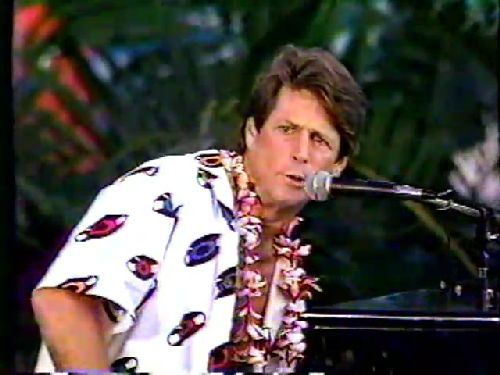

(Brian Wilson, Hawaii, Sept 1967)

May 16, 17, 18: The last designated Smile sessions, for Love To Say Dada. [1]

Also on May 17, The Beach Boys were in Germany, playing at the Sportshalle Cologne.

On May 19 The Beach Boys performed at Berliner Sportspalast. On the same day:

Gold Star Studio A, sessions cancelled without required notice period. Brian does not show at a session intended for Love To Say Dada. Capitol, tired of numerous delays with the album, is forced finally to abandon the recordings for Smile.[2]

So what did happen next?

One can only speculate upon conversations and discussions amongst The Beach Boys about Smile, its consequences and its aftermath, where there are not Capitol studio session sheets, memos, or contemporary interviews.

What does exist, and has seen print, can obviously be read in differing ways. Details may also be incorrect, dates may be awry…ultimately, it’s all a weird kind of fiction. Rock history thrives on ‘myths and legends’, and verisimilitude in this self-made, self-perpetuated saga might only be what seems to be true.

However, as a family, The Beach Boys obviously resolved some difficulties in private. And, alas, it’s only surviving members of that family lucky enough to have their memory still intact that know ‘what really happened’.

June 1: The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper album is released.

June 3: First Smiley Smile session, for Vegetables, at Hollywood Sound Recorders studio:

at Brian’s request most of the recordings made during the Smile sessions are now distinctly off-limits, and The Beach Boys find themselves in a bind for new material.[3]

June 5, 6, 7: Three further sessions for Vegetables are made at Western Recorders studio; June 7 is the last documented 1967 recording session in an outside studio. Cool Cool Water is started, but the track is left incomplete. [4]

On June 9,

a Beach Boys session is booked to start at 3:00pm today at Western studio 3; no further details are known.

By June 11, all work is now at Brian’s newly-installed home studio in Bel Air. [5]

June 12, 13, 14: Heroes & Villains is completely rerecorded for single release:

The Beach Boys complete the vocal and instrumental recordings (Master no.57020)…following Brian’s brief re-mixes and final edits,sessions for the songs are conclude. This time, his decision is final. [6]

June 16 – 18: The Monterey International Pop Festival takes place at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in California. John Philips of The Mamas and the Papas (a festival board member) tells the LA Times:

Brian was afraid that the hippies from San Francisco would think The Beach Boys were square and would boo them. [7]

June-July: The rest of Smiley Smile is recorded at Brian’s home studio.

July 14

The rocker Gettin’ Hungry (Master No.58027) is recorded and finished after 27 instrumental tracking takes, followed by instrumentation and vocal overdubbing by Brian and Mike. With that, the Smiley Smile album is completed (and dubbed down in just one night).

July 25: Capitol A&R director Karl Engemann circulates a memo discussing a 10-track Smile album, to follow the release of Smiley Smile. [8]

July 31: Heroes and Villains/You’re Welcome is released as The Beach Boys’ followup to Good Vibrations.

August 25 and 26: Concerts recorded at Honolulu International Centre for a live album, Lei’d in Hawaii. Brian Wilson performs with the band:

Unfortunately the taping is beset with technical difficulties, and the group decides that most of the recordings are not usable…according to those closely associated with the group, the problem that prevents the official release of this concert isn’t the recording quality but rather the somewhat mediocre performance.

Also on August 26, the Heroes and Villains single peaks at number 12 on the US Billboard chart.

August 28: Gettin’ Hungry is released as a single on Brother Records (through Capitol), credited to ‘Brian and Mike’. It fails to make either the US or the UK charts. [9]

On September 11, The Beach Boys use Wally Heider’s studio to rerecord new vocal parts to enhance the substandard Hawaii recordings, in order to complete a ‘live’ album suitable for release.

On this day Mike also records his Heroes & Villains ‘nuclear bomb’ monologue (‘Listen to these OUTSTANDING LYRICS! They’ll just amaze you, this nuclear disaster!‘). Lei’d in Hawaii is not released. [10]

September 18: the Smiley Smile album is released.

September 26: sessions commence for the Wild Honey album.

September 28: work is started on Can’t Wait Too Long [11]

October 14/15: At Wally Heider’s studio, Brian Wilson is in the studio with Redwood (Danny Hutton, Cory Wells and Chuck Negron), recording Darlin’ and Time To Get Alone (plus an unnamed third song). Darlin’ and Time To Get Alone were written by Brian specifically for the vocal trio, who are signed to The Beach Boys’ Brother label. These recordings are unreleased at the time, and both songs are rerecorded and released as Beach Boys singles. [12]

October 23: Wild Honey is released as a single; highest US chart placing #31, UK number 29.

late October: studio work is done for Cool Cool Water, Can’t Wait Too Long, Game of Love, Let The Wind Blow [13]

November 15: The Wild Honey recordings are completed.

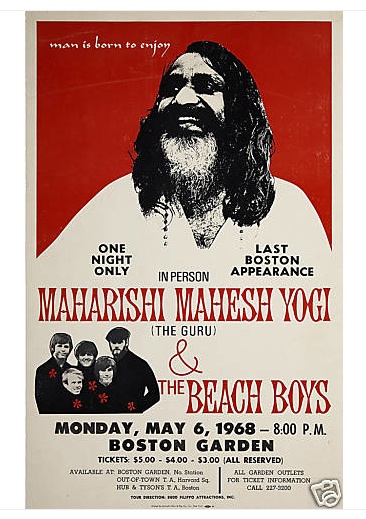

December 15: Mike Love, along with the rest of the touring Beach Boys, meets the Maharishi in Paris. Of this meeting, Mike later said:

the Maharishi gave us an introductory lecture and then, in the afternoon, gave us another talk, and then he taught us the techniques of Transcendental Meditation. It was the most relaxed I had ever been in my whole life..I was very relaxed and it was very simple to do. I remember thinking, ‘I wish everybody would do it’, because it is so simple and if everybody would do it, it would be a totally different world. So, from the very first time I meditated, I was intrigued by this. A couple of months later I found myself in India.

(from a 1973 interview with Scott Keller) [14]

December 18: The Wild Honey album is released;

highest US chart placing #24, UK number 7.

Notes on 1967

[1] Edited versions of the Love To Say Dada sessions are included in the 2011 Smile Sessions box; Brian certainly doesn’t sound like he knows that Smile is finished with. There is a playfulness to the announcement of each take, over both days of recordings. Brian affects a humorous voice, which he maintains throughout. The ‘Part Two, Second Day’ recordings (ie. 18th May 1967) also has an additional slide-whistle ‘birds singing’ development that suggests that this track is in process, with a finished version in mind.

That the Smile recordings were abandoned the next day does not appear to be reflected in the work the day before. And Smile ‘legend’ would have one believe that these sessions became increasingly weird, and increasingly ‘out of control’. But the recordings show the same Brian Wilson that all the Smile sessions reveal: a composer and a producer in control.

[2] With thousands of dollars spent on studio time for an overdue album, and with Brian working in the studio without The Beach Boys, who are in Europe promoting Good Vibrations, it’s safe to imagine that there were some lively Transatlantic telephone calls.

[3] Withholding Smile, and with the band having no immediate capacity to generate their own compositions or recordings, and with an album deadline well-overdue, and with the need for a suitable followup to Good Vibrations, Brian Wilson should have held considerably sway over the fate of The Beach Boys. For some reason he didn’t exercise that leverage. Or maybe he tried and failed.

There’s an odd moment in the October 2011 BBC Radio 4 interview with Brian promoting The Smile Sessions (as mentioned above): despite Brian stating that it was drugs that stopped Smile, the Front Row interviewer asks ‘what persuaded you to give up on it?‘

FR: …cos Mike Love your cousin –

Brian: – they didn’t like it FR: – he wasn’t keen on it –

Brian: The guys didn’t like it.

FR: Is that understated – they hated it at the time?

Brian: He was disgusted with it, he said “I’m DISGUSTED with this”, he said this is nothing like anything like a surf song or a car song or any kinda Beach Boy-type of song. I said “Mike. You gotta – if you don’t wanna grow, you shouldn’t live – if you don’t wanna grow, you shouldn’t live”. I said, “if you don’t wanna grow, you shouldn’t live”. (more here)

Brian’s reiteration of his response to Mike sounds, to me anyway, like a recollection rather than a reimagining. But even if it was a product of Brian’s own misremembering, it’s still pretty assertive – and quite specific:

if you don’t wanna grow, you shouldn’t live

I would imagine that, if Mike Love c.1967 were told something like this by Brian Wilson, Mike might, um, respond, maybe…?

[4] 2:21 of this Cool Cool Water session is included in the 2011 Smile Sessions release; the track was then abandoned, continued October 16, 26 and 29 1967, and then abandoned again. Part of the master take from the June 1967 session is used as the first minute of the version of the song, as released in 1970 – so whatever work and reworkings it underwent in its three-year gestation, some part of it was correct right from the start.

[Around] July 14th 1970, Warner A&R man Lenny Waronker decides to visit Brian at his Bellagio Road home in Bel Air. During the visit Brian plays Waronker a piano-and-vocal performance of Cool Cool Water, a song by Brian and Mike […] Waronker is moved by the song’s beautiful simplicity and insists that Brian include it on the group’s first album for the label.

Cool Cool Water, as originally recorded in 1967, sure as hell doesn’t sound like a Mike Love co-composition (although the Smile Sessions writing credits list it as a co-write). In the first session (Disc 4, Track 14 on The Smile Sessions) Mike is heard asking “is this the start of the song?”. Wouldn’t he know if he co-wrote it?

[5] So from now, and until further notice, Brian was no longer working in the familiar studios he has used for the last few years. Sporadic work using outside studios took place, but much of the Beach Boys’ recorded output over the next few years was constructed in Brian’s home.

One can only speculate on the reasons for this change.

However, contemporary reports suggest that Los Angeles studios were often quite social, and recording sessions had many people on ‘the scene’ dropping in, listening in…and Brian Wilson never appeared to be secretive about his work for The Beach Boys, never considered this a distraction, and never seemed to discourage these kinds of visits.

Visiting Brian at his own home/studio, after his ‘withdrawal’, would have been far more problematic – and certainly far less attractive – to his musical contemporaries (Mike’s post-Smile Beach Boys would have been there for starters…).

Some points that relate to this change of methodology, from the Brian Wilson – Songwriter 1962 – 1969 DVD.

Domenic Priore: (about Good Vibrations)

…it’s not just ‘the studio as an instrument’, that’s a vague saying – no, he knows the tone and the pitch like a string, or like you tune a guitar, you can tune echo in this room so it could sound this way. And he took the diversity of those rooms, and played them. That big studio is his guitar. Y’know? It’s REAL specific when they say ‘the studio as an instrument’- Brian Wilson was the only guy who ever really utilised this in such a way – in three different studios, at least, for Good Vibrations.

And later, about Brian’s work post-Smile

Hal Blaine:

I think he did lose his mind for a while, y’know, because we moved up to his house, we started recording…

they took a beautiful den, and put a board over the fireplace – that [the fireplace] was magnificent; up on the second story, they kind of cut out a little hole so they could talk to the band…

and we would record. But who was producing was Mike Love, and the rest of the guys, and it wasn’t Brian. And it wasn’t the same.

Peter Ames Carlin:

his bedroom was right above the studio, and he would lie in bed all day, not because he was spending his whole life in bed – he was going out at night, and partying with all his buddies – but he would lie there and listen to them record, and if he had any suggestions or ideas, he would either call them down, on his phone, or else he would put on his robe and shamble downstairs and suggest something…

So Brian’s familiar instruments, the studios where ‘he knows the tone and the pitch like a string‘, are replaced with impromptu baffles and boards in a spare room in his house?

Imagine you are Brian Wilson. And this is your house.

Try to visualise what Carlin says in bold (the emphasis is mine). While listening to Brian’s own In My Room, recorded four years earlier. And written when his bedroom was probably his only sanctuary.

Would you not also, eventually, lose your mind? I fucking know I would.

[6] The Unsurpassed Masters Smile Sessions bootleg box has some Heroes & Villains recordings, which session research now places as post-Smile recordings, being the process of constructing the new Beach Boys single. These sessions are not included on The Smile Sessions themselves as they were (ultimately) for Smiley Smile.

The Unsurpassed Masters bootleggers’ assumption was that these were Smile-era recordings; the seeming-ease that these multiple-vocal overdubs are laid down (the sessions are layer after layer of vocals) – wasn’t Brian too drug-addled to work after Smile‘s abandonment…? Obviously not.

He worked when he chose to, when he needed to. Capitol needed a single, so the Heroes and Villains ‘hitsville’ approximation was constructed in 3 days.

[7] In retrospect, and with hindsight, The Beach Boys would have seemed an unlikely, and possibly anachronistic part of the Monterey package. However a couple of earlier blog comments proffer a workable vision:

Imagine if they performed Smile at the Monterey Festival not unlike in the fashion of the Brian Wilson Presents SMiLE (possibly a more lively, psychedelic and natural performance which had all the boys and some of the Wrecking Crew). The world would be a very different place…I always imagine some grand stage show with the boys dressing up (like suits for Surf’s Up, Barbershop clothes for Heroes, psychedelic wear for Good Vibes, farm clothes for I’m in Great Shape thru Cabin Essence) and having some slightly animated Frank Holmes stuff going on in the background, and Van Dyke dancing on stage with an accordion or something.

Jimi Hendrix (and Otis Redding) get most of the Monterey glory for their ‘shock of the new’ – but imagine the above as witnessed by Otis & Jimi’s audience, the new Rock Music’s first sighting of the new Beach Boys…

[8] The Capitol Smile memo reads

After discussing a number of alternatives with Schwartz, Polley, and Brian Wilson, I agreed with Brian that the best course of action would be to not include [the Smile] booklet with the Smiley Smile package, but rather to hold it for the next album which would include the aforementioned 10 selections. The second album which would be packaged with the booklet would not include the selections Heroes and Villains and Vegetables. However, inasmuch as these two selections would have already been released, I believe the consumer would be quick to pick up the connection between the cartoon and these tracks. In fact, some word of explanation could be included in the liner notes of the second album.

(quoted in Brad Elliott’s The Facts About Smile, originally published 1984, reprinted 1988 in Look! Listen! Vibrate! Smile! p. 160)

So discussions about this projected and then abandoned version of Smile involved Brian Wilson, rather than The Beach Boys.

With the Smiley Smile album finished and scheduled for release, it’s difficult to imagine Mike Love (for instance) being particularly enthused about an album featuring Do You Like Worms, Cabin Essence and Surf’s Up sharing the record racks with Smiley Smile. She’s Goin’ Bald, Gettin’ Hungry and Whistle In might look a little pointless in comparison…Dennis and Carl Wilson ‘loved’ Smile (The Smile Sessions book uses quotes from both saying as such), and would undoubtedly have conceded to this slimmer Smile, if Brian approved it, and an audience accepted it.

And if any potential buyer had already bought both Good Vibrations and Heroes and Villains as 45s, it’s not difficult to imagine which album would be the more desirable purchase.

[9] See He’s Goin’ Bald & Gettin’ Hungry for comment on this particular track, and its role as a nail in the coffin (or a stake through the heart) of Brian Wilson’s Smile ambition.

[10] There is full transcript of Mike Love’s ‘live’ performance of Heroes & Villains here. These faked ‘Hawaii’ recordings were discovered in the tape vaults in the early 90s, and bootlegged in 1994. Prior to their rediscovery, they seem to have been unknown by bootleggers, and long-forgotten by The Beach Boys.

This track has undergone a few perceptual revisions since ’94:

To listeners, it appears that he’s mocking Brian’s song, and his talents, but Mike has since claimed that this overdub was all in jest, with his peculiar sense of humor biting a bit too close to the truth

(says beachboys.com, here).

Later it becomes a ‘skit’, and then, most amazingly of all, Brian Wilson becomes the author of its ‘script’.

There’s some commentary upon this disconnect here – but ‘according to various people who should know‘, it’s scripted, and, by implication, ‘all in jest’.

So this works how exactly? You really think that Mike Love (still rankling from the chart failure of a record he hated right from the start) needed a ‘script’ to exercise his schadenfreude, disdain and vitriol? You do?

The 1967 Beach Boys missed a trick by not releasing this recording. As a followup to the chart failure of Heroes & Villains, and with talk of the original single being in two parts, here’s an instant Part Two! Couple it with a You’re Welcome session from The Smile Sessions (15.12.66, disc 4, track 16, 6:18 onwards, where The Beach Boys’ vocals successfully impersonate tape flutter) – call it You’re Unwelcome…and there, on a 7″ single, would be Mike Love’s public ‘fuck you’ to Smile.

[11] Can’t Wait Too Long/Been Way Too Long was finally released in a couple of variants on the Smiley Smile/Wild Honey CD reissue in 1990, and on the Good Vibrations box in 1993. It would be nice to link to youtube audio, which has been up for years, but it was taken down (for obvious copyright infringement) a few months ago. It’s also no longer available digitally via Amazon, and is thus presumably also not available from any other digital outlet. Usefully the 1991/2001 ‘twofer’ CD is still available, and is currently the only place this longer edit can be heard.

The 1993 30 Years of the Beach Boys boxed set Good Vibrations is Used & New, and is still available digitally, so the second, shorter version of CWTL/BWTL can heard and bought here.

The Hawthorne, Ca. – Birthplace of a Musical Legacy 2CD compilation, as a Band Brand conceit, contains a 49 sec ‘acapella’ snippet, and a few more vocal snippets are included on 2013’s Made In California box set. But neither of the versions that best demonstrate what this track could have been in 1967 are acknowledged by 2013’s Beach Boys.

All of these Can’t Wait Too Long re-edits were pieced together by engineer Mark Linett, from segments that Brian never finished either recording or sequencing; it’s difficult to imagine this as a song as such – it’s more of a piece, but most definitely a composition. Any ‘final’ version could ultimately have been just repeated variations over two sides of an album…but, unfinished, it’s almost impossible to imagine what Brian Wilson’s intentions were. This unfinished/unfinishable aspect of Brian’s post-Smile work is often cited as indicative (or even symptomatic) of some kind of ‘madness’.

But what if Pet Sounds had been rock history’s ‘great lost album’? The same could be said of Pet Sounds‘ instrumental tracks before the group’s vocals were added.

[12] According to Badman,

The Redwood/Brother deal will apparently be called off by Mike who feels that the group should be signed to the label for just one single. According to Beach Boys historians, Redwood’s material is left unreleased because Mike feels that the group’s vocals are not good enough.

Other accounts exist:

[Redwood] were just starting to work on the vocal tracks when Carl and Mike walked through the door of the Wally Heider studio where they were working, looking anything but happy. “Mike got us outside and said ‘Hey, what’s going on? we’ve got an album to do. Why don’t you wrap this up?'” Hutton recalls. “And Brian was physically afraid of Mike. Not that Mike used to beat him up, but he’s a tough guy physically, and Brian wasn’t like that, so Mike could definitely push him around mentally.”

(Peter Ames Carlin, Catch A Wave, p.130)

And, from Chuck Negron’s own memoir Three Dog Nightmare:

To me, Mike seemed an arrogant, self-serving guy, and when he walked in, it was as if a black cloud had suddenly surrounded Brian. I figured I would try to break the tension. Mike was wearing an expensive cashmere overcoat, and I said, “Wow, that’s a beautiful jacket.” He turned towards me and, in a condescending tone, answered, “Well, you just keep trying to do the right thing and maybe you’ll get one too, man.”

Later I heard he was bad-mouthing us to Brian, saying, “They’re nothing.” It soon became clear that Mike Love and the other Beach Boys wanted Brian’s immense songwriting and producing talents used strictly to enhance their own careers […] It all came to a head several weeks later when Mike heard our version of Time To Get Alone…they manouevred Brian into the control booth and reduced him to tears. It was a cruel and pathetic scene. Danny, Cory and I were in the studio and could see it happening through the control-booth window. It was as if Brian had turned into a little boy. The conversation appeared quiet and calm, but we could tell it was emotional and intense. The others were doing most of the talking, like overbearing, controlling parents. Brian would move away, and they would block his escape. We couldn’t hear what was being said, but I think a good lip-reader would have picked up something like, “We don’t give a shit about those guys, and we want those songs for us.” we could actually feel Brian crumbling, and when he came out of the booth, a tear dropped down his cheek. His head was lowered and his shoulders sagged. it was the body language of a child who had just been scolded and punished. And this brilliant musical icon – whose songs defined on generation and influenced another – weepingly told us, “We can’t do this. I have to give the songs to them. They’re family and I have to take care of my family. They want the songs. I’ll give you any amount of money you want to finish an album, but I can’t produce it. They won’t let me.”

(quoted by Domenic Priore in Smile – The Story of Brian Wilson’s Lost Masterpiece, p. 128-9)

The Redwood version of Time To Get Alone is here (although this version is missing the brief orchestral reprise). It’s a great example of what kind of work Brian Wilson could have done, were there no Beach Boys, and had he continued making music as a writer/producer. It has a few production/arrangement quirks that The Beach Boys’ own version didn’t use. The Redwood version is, frankly, a more interesting recording.

Comparing the two versions, an overfamiliarity with The Beach Boys’ cover of Time To Get Alone creates an odd disconnect: in this single track is the basis of a Beach Boys album style that, in 1967, didn’t even exist; snapped up by Mike and co and assimilated by the band, what Brian was creating for Redwood was intentionally separate from his day job as Beach Boys writer/producer.

After leaving Brother Records without a release, Redwood became Three Dog Night soon after, and were hugely successful in the US (although kind of meaningless in the UK). Mike Love, in an uncharacteristically magnanimous admission, said in 1976

The thing is, that was one of the stupidest fuckups in the world of recording. Three Dog Night sold more records, singles that is, than anyone in the world, and Brian Wilson produced them originally

but then turns this around:

…but you know, it was funny. They’d go in, and they wouldn’t sing good enough for him; he didn’t want to hear any sharps or flats; he was at that period in his life when he was horrible to live with. But he’s great musically…the fact of the matter is that he had them in the studio for several days, and he was really funny. They didn’t meet up to his expectations, but they went off and made billions.

(from Mike Love: 14 Mins With A Beach Boy by John Tobler, reprinted in Back To The Beach, p.151)

So there was a fuckup – but it was Brian’s rather than Mike’s. Stupid stupid Brian – who ‘was at that period in his life when he was horrible to live with’; ‘that period’ being six months or so after his greatest work was discarded. That might have had some bearing upon his mood…but who knows.

Which one of these accounts is true? Which version of events has any verisimilitude? And which doesn’t?

Three Dog Night pop up at the monstrous 1987 25 Years of The Beach Boys – A Celebration at Waikiki cited above (minus Chuck Negron, out of the band for drug indiscretions); Brian Wilson and Two Dog Night sing Darlin’, as originally written and produced for Redwood by Brian. As Darlin’ was also co-opted and rerecorded by The Beach Boys, Danny Hutton and Cory Wells are singing a cover version of their own unreleased song, in tribute to the longevity of The Beach Boys.

[13] This seems like a productive few days. Were the Beach Boys in attendance, or was Brian working on his own impetus? Of the four songs logged, only Let The Wind Blow was released on the album the Beach Boys were recording. Was the 1967 Surf’s Up, a previously unheard bonus track on The Smile Sessions (which was on the same reel of tape as versions of Let The Wind Blow) also recorded at this time?

[14] From this point on, and until further notice, The Beach Boys’ destiny became bound to the ‘discipline’ of TM. The ‘spiritual enlightenment’ offered by Transcendental Meditation changed the fate and the fortunes of The Beach Boys, for years to come. Mike Love, as the band’s (the world’s?) most vocal adherent of Transcendental Meditation, has kept TM as a Beach Boys ‘theme’ since.

So, post-Smile, 1967 in summary seems to show a Brian Wilson somewhat at odds with the caricature The Official Narrative favours: someone that was able to continue functioning – as a person, as a composer, and as a producer. What he seemed least able to do, and least willing to be, was to continue being a Beach Boy.

And in 1968?

1968.

(Brian Wilson, at home, 1968)

February:

Friends session 1, Brian’s Home Studio, Bel Air, CA. During this month Brian records an early version of When A Man Needs A Woman and a backing track for You’re As Cool As You Can Be, which will remain unreleased. Another backing track recorded for Brother this month, I’m Confessin’, may or may not be intended for The Beach Boys. [1]

February 1 to 11: The Beach Boys play some smaller gigs, in Washington State, British Columbia, Portland Oregon, and at the International Ice Palace, Las Vegas.

February 16: back from touring, a Beach Boys studio session is cancelled.

February 17: The Beach Boys are at The Pawtuxet Ballroom, in Cranston, Rhode Island

February 28 to March 15: Mike is in India with The Beatles. On Mike’s birthday, The Beatles sing him ‘happy birthday’. The event is recorded by a film crew. In 2004 the audio recording is retitled Thank You, and is included on Mike’s (still unreleased) Unleash The Love album. [2]

April 4: Transcendental Meditation is recorded. Also, a planned US tour is either cancelled or rescheduled after the assassination of Martin Luther King. [3]

April 6: Dennis Wilson ‘crosses paths’ with two of Charles Manson’s girls for the first time.

April 11: Dennis Wilson crosses paths with Charles Manson for the first time. Brian records Busy Doin’ Nothing. No other Beach Boys participate.[4]

April 12: Diamond Head is recorded by Brian at ID Sound Studio Hollywood; meanwhile The Beach Boys play at Jacksonville Coliseum, Florida.

April 13: Be Still is recorded; the Friends album is complete.

April 14 to 27: The Beach Boys play various rescheduled dates on their projected tour. The band have so far lost $350,000 dollars in expected revenue after their tour cancellation.

May 2: A new tour is started – The Beach Boys will play 17 shows, with the Maharishi as support, lecturing audiences on Transcendental Meditation.

May 4: The tour is not a success thus far: an afternoon show in Flushing NY is cancelled after the 16,000 capacity venue sells only 800 tickets; and

a spokesman for the 17,162-seater [Philadelphia] Spectrum says “the Guru couldn’t draw flies. Tickets went out for just $5 and $3 and people walked out before and during the Guru’s lecture. The attendance was about 5,800.”

May 5: The Maharishi leaves the Beach Boys’ tour to fulfill a movie contract.

May 6:

The TM tour is cancelled after 7 shows, due to poor ticket sales, plus the loss of the Maharishi to other commitments. The band lose another $500,000 in revenue.

May 11: Penny Valentine writes in today’s (UK) Disc & Music Echo:

“A carefully calculated warning to The Beach Boys — split up or get yourself together. There is something very stale in The Beach Boys camp. It is the smell of utter freedom run amok. It is the smell of staleness and inertia.

“It is not pleasant to reflect upon The Beach Boys and see what could have been and then face what is…This fact has been brought home to me by the group`s latest release. ‘Friends’ is about the ultimate in sadness. Whither the progressive Beach Boys? Whither the same spine·tingling sensation one got from ‘God Only Knows’, The Beach Boys’ answer to The Four Tops’ ‘Reach Out’? Gone, gone, gone. It has been suffocated in the same boring, muffled voices, the same trivial words, the same droning friendly-dull atmosphere.

“If The Beach Boys are as bored as they sound, they should stop bothering and retreat to the Californian foothills. If they`re not, they should stop boring their public and insulting them with below-par performances. Three years ago The Beach Boys gave us the the throttled heady taste of Californian summer. The sun always shining, the surf always coming into land, brown young bodies on a beach, summery love in the long grass. They gave it to us through a record, frothy as the top of a Coca-Cola and burning as a 350cc Honda. They had a hardcore following here in gritty England, a mammoth one in America. Their final and complete connection with the public came with ‘God Only Knows’, ‘Good Vibrations’ and the beautiful Pet Sounds. It turned out to be their zenith.

“They had started something new and thrilling — a great kick in the stomach for pop music. Brian Wilson was lauded and acclaimed with all the power we could muster. But instead of leading us on to newer and more exciting things, they began a steady plunge downhill. Instead of thrusting us upwards, they led us no round the maypole with nonsense like ‘Then I Kissed Her’.

“Today, The Beach Boys are floundering pathetically in a mire of stodgy apathy. It is now time for them to stand still and take stock of themselves and the situation they are in today. They have been given too much freedom. Like greedy schoolboys in a sweetshop their sense has not prevailed -— their control has snapped. They are no longer the brilliant Beach Boys. They are grey and they are making sad little grey records.”

May 24: Recording of All I Want To Do commences, beginning the sessions for the 20/20 album.

May 26: sessions begin for Do It Again.

June 5: Brian records I Went To Sleep.

June 20: Bruce records his instrumental track The Nearest Faraway Place.

June 24: The Friends album is released.

It sells in the UK (highest chart placing number 13), but fails to make any impact in the US (highest chart placing # 126):

from now, [Brian Wilson’s] influence on future Beach Boys recordings will falter at an alarming rate.

(says Keith Badman)

July: Charles Manson records in Brian Wilson’s home studio [5]

July 2 to Aug 24: The Beach Boys tour again.

July 8: Do It Again is released as a single – it is a hit, but the band’s last for 8 years.

July 24/26: Brian does more work on Can’t Wait Too Long, without the other Beach Boys.

August: Dennis Wilson moves out of his house to get away from Charles Manson’s influence.

September/October: Recordings – Never Learn Not To Love (aka Cease To Exist by Charles Manson, Dennis’ choice), I Can Hear Music (Carl’s choice, a cover version), Time To Get Alone (their rerecording of Redwood’s song)

November: Recordings – Bluebirds Over The Mountains (Bruce’s choice, a cover version), Cottonfields (Al’s choice, the Leadbelly song)

November 17: The Smile track Prayer has vocal overdubs added to it – it becomes Our Prayer. Brian Wilson is not involved in these recordings.

November 20, 21, 22: The Smile track Cabin Essence is sequenced and has vocal overdubs added – it becomes Cabinessence. Brian Wilson is not involved in these recordings.

With the completion of Cabinessence, recordings for the 20/20 album are finished. [6]

November 29: The Beach Boys begin a tour of the UK and then Europe. Penny Valentine (in the UK Disc & Music Echo) says of their current single Bluebirds Over The Mountains:

it’s probably the strangest record The Beach Boys have ever made. It really is so odd, disjointed and confusing. I can only see it being a hit because they’re here in person.

The single is a UK number 33, and a US #61.

December 2: With The Beach Boys in the UK, Brian Wilson records Come To Me with The Honeys (ie. his wife and her sister & their cousin).

December 13: Further recordings with The Honeys – Tonight You Belong To Me and Goodnight My Love (Pleasant Dreams). Capitol release these recordings in March 1969, but the single fails to chart. [7]

Notes on 1968

[1] More studio work without The Beach Boys, more Brian Wilson music that remains incomplete or abandoned. It is almost impossible to know why so much music written and recorded by Brian, in the absence of the touring band, seemed to get left unfinished. But it’s always possible that it was deemed ‘inappropriate for The Beach Boys’ – or maybe deemed ‘inappropriate’ by The Beach Boys…as a collective entity, the band seemed much surer of what it didn’t want to be than what it was, or could become.

If productions and compositions were knocked back by the band or an outspoken band member, or if solo work then became ‘collaborative’ once other contributions were made, one could imagine a certain ‘oh fuck it’ attitude might develop in Brian Wilson’s creative method. Indeed; why bother?

[2] The Beatles seem to mean a great deal to Mike Love. Brian was the competitive one, whereas Mike and The Boys (minus Brian) met The Beatles in London in 1966, and then Mike had his formative spiritual experiences in their company in India in 1968.

Fast forward to 2012, and Mike’s facebook page seems to favour The Beatles over The Beach Boys (and Dennis over Brian):

(snapshot March 2012)

Bruce Johnston talks about London in 1966 on the Brian Wilson – Songwriter DVD, and it’s touching how much it obviously meant to him – but he only became a Beach Boy months before; nothing in the job description would have prepared him. He retains the enthusiasms of a fan meeting his idols, even in his old age.

In the October 2011 BBC Radio 4 interview, Brian Wilson is asked about a specific Smile session:

FR: …there are some guest appearances in there, most notably Paul McCartney

Brian: Right

FR: – is said to have munched a celery stick on the track Vegetables

Brian: Right!

FR: – I’ve been listening for that, I couldn’t hear…it’s always been billed as a celery stick sound –

Brian: – you’d have to sit down and listen to all those tapes we made in order to find that one little part y’know…(Vega-Tables is heard, with chomping)

Brian: (continuing) He was improvising, yeah

FR: So can you remember that session?

Brian: (pauses) No I can’t. No.

Brian’s own ‘collaboration’ with A Sainted Beatle has rather more substance than Mike’s impromptu ‘Happy Birthday’, captured accidentally, and then brandished as trophy tribute right through to the 21st century – and should also have been more momentous, were Brian himself not more preoccupied with the work itself…

Mike’s attachment to The Beatles thus seems a little more mysterious. I do not recall one interview or quote where he speaks of The Beatles in isolation from The Beach Boys, apart from in India with The Maharishi. And while he will talk about the latter unprompted, has he named a single Beatles song (apart from Back In The USSR, with Mike as ‘inspiration’) that means anything to him?

Does Mike champion The Beatles so because they ‘beat’ Brian? Once Sgt Pepper was released, maybe nothing Brian could do could ever match them. Sgt Pepper curtailed Brian’s ambition with Smile – but, without discouragement, his ambitions might have recovered. They didn’t.

Was this then, and remains so to this day, in some mysterious way satisfying for Mike?

[3] There’s an impassioned fictional monologue in The Beach Boys: An America Family ‘official’ TV drama, from a hirsute and serene ‘Mike Love’, to his philistine girlfriend:

There is too much bad karma out there. Look around: King, Kennedy, everybody with a message of hope gets cut down – meditating is so simple anyone can do it, and if everyone did it the world would be a totally different place. You won’t KNOW unless you try.

This generously-thatched Mike Love takes Martin Luther King’s assassination as a depressing manifestation of a negative world and a destructive worldview. Would it be uncharitable to consider the burgeoning Beach Boys Corporate identity to be rather less altruistic about their cancelled tour’s financial losses at the time?

[4] ‘No other Beach Boys participate’ is a recurring phrase in Brad Elliott’s Friends Era Chronology (in The Dumb Angel Gazette #3, 1989). Anti-Smile‘s various mythologies (usually perpetuated via the band’s mawkish TV and video self-celebrations) have Brian unable to write or perform, while simultaneously creating chunks of Friends with The Beach Boys absent. Obviously you can’t have it both ways. Or maybe you can.

[5] from The Definitive Diary:

Charles Manson, who hopes that Brian can work wonders with his musical career, tapes a number of recordings intermittently during this period at Brian’s Home Studio, allegedly co-produced by Brian and Carl. Dennis plays some part in the proceedings, as do members of the so-called Wrecking Crew, the elite team of LA studio musicians used by Brian, Phil Spector and others.

Nick Grillo will recall in Rolling Stone, “We recorded close to a hundred hours of Charlie’s music at Brian’s studio. The lyrics were so twisted and jaded.”

Charles Manson says in Rolling Stone that they “did a pretty fair session, putting down about ten songs”.

Steve Desper who engineers the sessions, remembers that some of the material is “pretty good [Manson] had musical talent.” Desper, who supervises three or four late-night recording sessions by Manson, thinks of Manson simply as a ‘street musician’ friend of Dennis’ and reckons that Manson is desperately in need of a good long bath.

Contrary to the writings of later rock revisionists, the songs taped by Manson are not demos but completed songs — or at least are as complete as Manson wants them to be. Reportedly, he rarely records more than one take of a vocal.

The precise titles recorded are not known, but it’s safe to assume that they are the same songs that will appear later in different form on his Lie album, released not long after Manson’s arrest following the Sharon Tate murders in summer 1969 but recorded sometime during 1968/69, shortly after he falls out with Dennis. The songs on that album are ‘Look At Your Game Girl’, ‘Ego’, ‘I Am A Mechanical Man’, ‘People Say I’m No Good’, “Home Is Where You’re Happy’, ‘Arkansas’, ‘Always Is Always Forever’, ‘Garbage Dump’, ‘Don’t Do Anything Illegal’, ‘Sick City’, ‘Cease Tb Exist’, ‘Clang Bang Clang’, ‘I Once Knew A Man’, and ‘Eyes Of The Dreamer’.

The versions on the ‘Lie’ album are not the Brian’s Home Studio recordings. In 1971, when Manson murders investigating officer Vincent Bugliosi of the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office asks Dennis if he can listen to the musical tapes Manson made, Dennis claims he has destroyed them because “the vibrations connected with them didn’t belong on this earth”.

Charles Manson, like most charismatic celebrity psychopaths, holds a fascination for some people, to this day. And while members of Manson’s ‘family’ are still incarcerated, the story itself won’t go away – the LA Times reported in October 2012 the LAPD probing Manson family link to 12 unsolved homicides:

The Los Angeles Police Department disclosed Thursday that it has open investigations on a dozen unsolved homicides that occurred near places where the Manson family operated during its slew of murders four decades ago.

A reader’s comment on that story:

charles manson is awesome ! leave him alone fuvk

Etc.

My own (brief) interest in Manson in the mid-80s eventually lead to to The Beach Boys, 20/20, Cabinessence, and ultimately to Smile itself.

LIE, Awareness Records, 1970 (from here)

It seems, in retrospect, extraordinarily-poor judgement on the part of Dennis Wilson to indulge Manson’s musical pursuits – but, if one actually listens to the LIE album, there was far worse, less competent, less interesting music being made by Manson’s professional musical contemporaries. And if your tastes lean towards the creepy psychopathic troubadour, try Dino Valenti’s Dino Valente album from 1968. This is music made by a man no woman should ever risk being alone with – surely…

One could even argue that, had these now-missing Brother recordings been released (maybe by Brother Records themselves), Charles Manson would join the pantheon of ‘lost psych-folk classics’ now so fetishised by record nerds. But that’s a pointless and defensively-hypothetical argument for Manson as ‘personality’.

Strangely, psychopaths often attract followers, apologists, shills…what are those who defend poor music made by vile and arrogant ‘classic’ artists? And, cults, brutal murders, and a purported apocalyptic vision of a coming race war apart, does Manson, as aspiring artist, differ that much from some of the egotistical scumbags that now clutter the reissue racks and the ‘rock classics’ canon?

Psychopathy, contrary to anything Hollywood might say otherwise, rarely involves actually killing people; having a callous unconcern for the feelings of others – combined with an inability to experience guilt – just makes killing people easier. It’s a useful byproduct of being a psychopath – but not by any means an essential part of the job description. Manson himself, in a different milieu, could have used his notorious ‘people skills’ to become extraordinarily-successful corporate CEO.

And, if one wanted to be pedantic about what Charles Manson did and didn’t do, the attribution of personal responsibility for the murders of Sharon Tate et al to Manson himself is kind of moot: he wasn’t even in in attendance at Cielo Drive, and only tied up the LaBiancas, leaving their slaughter to his followers.

Manson is, bizarrely, available for comment – you can write to him in prison, and people have done. Here, a prison letter from 2007 is reproduced, where historical celebrity dirt is solicited:

Having been a gossip columnist, as well as an investigative reporter, I had often asked Charles to name some of his Hollywood friends.

Manson reminisces about life at Dennis Wilson’s beach house:

Neil Diamond used to come over, Mike Love of the Beachboys, Doris Day’s son, Angela Lansbury’s daughter, DeeDee, Nancy Sinatra’s daughter used to be at the beach pad. Dennis Wilson of (the Beach Boys) & I lived with 15 or 20 of the best. We kicked Jane Fonda out of that dream because her jewish boyfriend wanted to bring a black guy to play ping-pong with her & I said I don’t play mixing blood for phony christians that work for their money selling children. She had a big dog and a crummy camera & I said no no, I do what I do for love, not money.

It goes on and on. And on. And makes many unqualifiable statements about other second-rate or long-dead LA celebs.

Brian Wilson’s Todd Gold-authored ‘autobiography’ Wouldn’t It be Nice has a Manson story not recounted anywhere else:

The tales Dennis told made it seem as if he were living the life of Riley, which was more than enough to interest Mike. Although he was always wary of Manson, the notion of easy sex once enticed Mike up to a dinner party at Dennis’s house. Walking in with his date, Mike found the dining room table overflowing with food and the entire Manson family sitting around the table wearing absolutely nothing. They were stark naked.

“I’ve never been into group sex,” he mentioned as he told me the story. “Well, maybe two women.”

After dinner, according to Mike, the activity began to heat up and Mike slipped upstairs with his date.

“I was having a good time in the shower with this little chiquita,” he continued. “We were getting into it, washing each other. Suddenly the shower door swings open and standing there is Charlie Manson. I didn’t know if he was Jesus Christ or the devil, but there was fire in his eyes. Manson stood there, looking at us, and then said, ‘You must come down and join the party.’ Then he closed the door and left. Well, we finished up and split. Wasn’t my kind of party.”

With that book’s reputation, this is probably about as reliable as Manson’s own suggestion that Mike Love might been a more frequent visitor to Dennis’ co-opted beach house than reported. Funny story though.

The Manson saga, and Dennis Wilson’s connections to it, is obviously covered in much more (legitimate) detail elsewhere. The earliest published accounts of the Manson Family’s history and activities are Ed Sanders’ The Family: The Story of Charles Manson’s Dune Buggy Attack Battalion (1971) and Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter (published 1974. Here the Beach Boys’ fan community provide some comments about the reliability of declared Beach Boys/Manson connections, and usefully points any curious reader away from Tommy Udo’s Music Mayhem Murder book from 2002 (‘This was probably the most factually inaccurate book ever published‘ – what, on any topic?).

Nicholas Schreck‘s The Manson File (originally published in 1988; a hugely-expanded edition was published last year) looks to be the most extensive and most definitive study to date; and Schreck’s research and revisionism proposes a rather different explanation of ‘The Manson Murders’ than the story perpetrated and perpetuated by Vincent Bugliosi in Helter Skelter.

Hear, should one wish, a long (3 hours) and engrossing telephone interview with The Manson File‘s author here – Schreck’s personal research is extensive, and, on the basis of the radio interview alone, may shed light on a rather larger crossover between the Manson Family and the LA entertainment industry than the latter might lead one to believe. Read, should one wish, Dave McGowan‘s Strange but Mostly True Story of Laurel Canyon and the Birth of the Hippie Generation (in 21 parts!) for a deeper look into LA’s darker history (or wait for 2014’s print version).

Manson was always a small, but deeply unfortunate part of Beach Boys’ lore, but history now attributes the Manson connection to Dennis Wilson alone.

And while Dennis stopped answering journalist’s questions about it all quite soon after the murders in August 1969, ‘another Beach Boy, an anonymous one, is a little more talkative about it’:

We’ve got several eight track tapes of Charlie and the girls that Dennis cut, maybe even some 16 track. Just chanting, fucking, sucking, balling…Maybe we’ll put it out in the Fall. Call it ‘Death Row’.

It was a million laughs, believe me.

(from Tales Of Hawthorne by Tom Nolan, Rolling Stone 1971, reprinted in Back To The Beach; Keith Badman & Peter Ames Carlin reprint the same quote, but attribute it to Mike Love)

Imagine for a moment that you are Brian Wilson. And these recordings were made in your house, your studio, below your bedroom. Imagine that, in some innocence, you contributed – but, unlike your brother (or cousin, if one chooses to believe Manson himself), you didn’t fuck any of of the Manson girls. And then you discover, along with the rest of America, that Charles Manson and his ‘family’ are accused of committing these murders.

Try to visualise what a wry and dry Mike Love says above. While listening to Brian’s own In My Room, recorded five years earlier. Etc.

[6] In contrast to Brian’s own work alone, on sessions and tracks for Friends and 20/20, he does not appear to have been involved in the retrieval and reclamation of Prayer and Cabin Essence. That both tracks have survived intact, with some extra vocal overdubs on the former (plus its possessive retitling), and the new lead vocals (and final resequencing) of the latter, is probably only a reflection of the close-to-completion state of these session tapes.

It would be an error to consider that this Brianless band work was done with any reverence for the integrity of either track. 20/20 is, after all, the same album featuring Bluebirds Over The Mountain, Cottonfields, The Nearest Faraway Place…all mediocre (in comparison to The Beach Boys pre-67, and every other ‘rock artist’ post-67), all nonetheless deemed worthy of release.

That both Cabin Essence and Prayer somehow slipped out, and into an indifferent world – as a microcosm of Smile – is fortuitous indeed. That the ‘acid illiteration’ of ‘over and over the crow cries‘, sung in 1968 by the Beach Boy who objected to it so vociferously in ’66…well, that’s kind of surprising: Cabin Essence, and it’s ‘meaninglessness’ to Mike Love, should really have precluded any future participation by its strongest critic. But there they are, as the last lines of Cabinessence, the last track on The Beach Boys’ last studio album for Capitol Records.

‘Over and over the crow cries, uncover the cornfield‘ thus becomes, in essence, the last words sung by the sixties Beach Boys.

Did something change Mike’s mind about the quality of that song? Subsequent history says otherwise.

Mike may maintain that the lyric was the issue; that he contributed to the completion of Cabinessence might imply that his issue was maybe with its lyricist instead.

[7] The Honeys, being Brian Wilson’s wife, her sister and their cousin, were obviously an easily-accessible ‘instrument’. The Beach Boys own ambitions and aims, for the band under their control rather than Brian’s, probably meant that a Honeys session, where Brian Wilson is acknowledged as the writer, arranger and producer, and is deferred to as such, could maybe be more personally satisfying, and rather more free of the ‘creative tensions’ that a 1968 Beach Boys session might have. To borrow one of Mike Love’s time-reversing 2012 statements, it might even feel like ‘1965 all over again’…that is, that Brian Wilson’s role in the studio might be treated with the deference this job demands.

That the resultant tracks weren’t a hit might not have mattered; that these sessions even got released at all seems slightly surprising: it was probably only the fact that both songs were covers that precluded The Beach Boys immediately co-opting and rerecording them as band singles.

So that was 1968.

Yeah, there is Friends, a small album with small glimmers of Brian Wilson’s previous skills manifest throughout (and more directly in the instrumental track Diamond Head) – but, as seen by Mike Love’s the band’s possessive behaviour over Redwood’s song Time To Get Alone (and their own structurally-inferior version), it’s hard not to come to the conclusion that, wherever Brian’s musical ideas strayed, even for a second, outside the rubric of what The Beach Boys was supposed to be, work on interesting tracks like Can’t Wait Too Long or Cool Cool Water seems to have been curtailed in favour of more digestible, containable, and substantially less adventurous (failed) stabs at the pop charts.

21st century fans seen to value these failures – failures of ambition, of execution, commercial failures…the history of the band, post-67, has long periods of these kinds of failures, peppered with an occasional success – ‘sad little grey records’; prior to 1967, their career was the diametric opposite of this.

Penny Valentine’s 1968 review of the UK Then I Kissed Her single says a great deal about how disappointing Beach Boys releases had become since Good Vibrations. While what she writes doesn’t acknowledge Then I Kissed Her as a pre-Pet Sounds recording, there is the tacit dismissal of both Smiley Smile and Wild Honey as wanting. When she describes Friends as ‘about the ultimate in sadness’, this perceived pathos is obviously in what the music lacks. Whither the progressive Beach Boys?

But isn’t the ‘staleness and inertia’ she berates strangely coincident with the point that Brian Wilson relinquished control of The Beach Boys to…well, The Beach Boys themselves? While Friends is more obviously a Brian Wilson album than, say, 1972’s Carl And The Passions, it suggests more where it sounds least like The Beach Boys. Even Transcendental Meditation has come to sound like some odd precursor of Faust (listen to that crazy saxophone!).

Had Friends included a Can’t Wait Too Long variant (as projected), it would have been a different album. Instead, in its sweetness, it’s mostly twee, trite and slight. And brief: its total running time is less than half an hour, but there was enough music recorded at the same time to give it a far less derisory length. Another instance of the lacksadaisical hubris of the band at the time: ‘fuck it, this’ll do’.

Audience expectations of pop albums continued to develop after Sgt Pepper. It’s not difficult to imagine Penny Valentine or her readership playing Friends, and then thinking ‘that’s it?!?’ Whither the progressive Beach Boys etc.

The band, as an entity, were maybe at their lowest ebb in ’68. And ’69. Oh, and 1970…as Carl says above, ‘we felt as if we’d been passed by’. The only thing keeping the Beach Boys brand alive at this time was inertia, and maybe a sense of, I dunno…entitlement? I mean, what else could they do? Would Mike Love relinquish the stage, the attention, maybe moderate his ostentation, accept his creative limitations, or even retreat into his meditation? Fuck no. Give all this up?!?

1969 was a big year for the Beach Boys’ public profile. Little that transpired, however, could be considered ‘good publicity’…

1969.

(Mike Love & Brian Wilson, in the studio, July 1969)

January 15: The Beach Boys begin another set of US concert dates.

February 10: The 20/20 album is released. Two 1966 Smile tracks (Prayer and Cabin-Essence) are released here in completed versions. [1]

March 31: Breakaway is recorded as a single, co-written by Murry Wilson, the father of The Beach Boys and their former manager:

by now the group probably know that this is likely to be The Beach Boys’ last single for Capitol, as they are about to leave the label. Eager to leave on a high note, Brian rises to the challenge and becomes involves in the song’s production, swiftly devising an impressive recording.

Released as a single in June, it is not a US hit, peaking at #63, although it reaches number 6 in the UK charts. [2]

May 27: Brian Wilson announces at a press conference that The Beach Boys are close to (financial) bankruptcy :

He says: “The Beach Boys’ empire is crumbling and in deep financial trouble…it’s got so bad that The Beach Boys are considering financial bankruptcy. We owe everyone money, and if we don’t pick ourselves off our backsides and have a hit record soon we will be in worse trouble. Nick Grillo, our business manager, says that if we don’t start climbing out of the mess he will have to file bankcruptcy in Los Angeles by the end of the year. Things started deteriorating about 18 months ago. Thousands of dollars were being frittered away and thrown away on stupid things…recently Nick told us how bad it really was. It was a big shock for us all. A really tough blow…I’ve always said be honest with the fans and I don’t see why I should lie and say everything is rosy when it’s not…the Beach Boys’ tour of Britain must be a success if the group is to survive.” [3]

May 30 to June 30: The Beach Boys depart for another UK/Europe tour

May 31: The Beach Boys play London’s Hammersmith Odeon. From David Hughes’ review of the concert in Disc and Music Echo:

Mike Love has grown his beard, grown his hair (on those parts of head where it still grows, that is) and has acquired an incredible white tunic/mini-habit. The overall effect is a cross between the Maharishi’s younger brother and the original hermit from the hills. All very incongruous, especially when he bursts into ‘well the East Coast girls are hip, I really dig those clothes they wear’. Mike has always looked the misfit in the group and gives the impression on stage that he doesn’t really know what he’s doing up there. His ad libs with the audience are becoming more and more outspoken.

June 8: The Beach Boys play Leeds Infirmary, with celebrated UK DJ Jimmy Savile in attendance. [4]

June 25 to 29: The Beach Boys spend time at a UK TM retreat. During this time Mike lectures a New Musical Express reporter about Transcendental Meditation:

I listened intrigued to Mike’s views on meditation and his beliefs in the teaching of the Maharishi…his conversation with the woman who studied life-after-death was captivating. Talk evolved about the planets, which Mike is currently writing a song about. But I must admit, a lot of it left me cold. [5]

June 20: The band’s contract with Capitol Records is fulfilled. The band are now without a record contract.

July 1: No other record company seems immediately keen to sign The Beach Boys – a deal with Deutsche Gramophon falls through, in part because of their wariness of the band’s financial needs, presumably via a notification of their financial state by Brian Wilson at the press conference in May. [6]

August: Brian Wilson records an album, in his home studio, A World Of Peace Must Come, for Steve Kalinich, a poet who also co-wrote Beach Boys songs with Dennis Wilson. It remains unreleased until 2008. [7]

August 9: The Tate murders.

August 10: The LaBianca murders. [8]

September: an interview with Dennis Wilson, given prior to the events of Aug 9 & 10, is published in Rave Magazine in the UK, which mentions Charles Manson as ‘The Wizard’, a mixture of musical associate and personal guru.

November 4: Brian Wilson records a solo piano demo for a first draft of Til I Die. [9]

November 18: The Beach Boys eventually sign with Reprise/Warner Brothers, after the intervention of Van Dyke Parks, on their behalf, defending the band as ‘an American institution’. Their contract is for $250,000 per album, and the label insists that Brian Wilson be involved in all future recordings. The same day, Murry Wilson sells off the entire Sea Of Tunes publishing catalogue – the publishing for all of Brian Wilson’s songs – for $700,000.

Studio sessions over the next few months are for the band’s Reprise debut ‘offering’. [10]

Notes on 1969

[1] Rolling Stone, as post-Monterey tastemaker for the ‘rock revolution’, describes Cabinessence in its contemporary 20/20 review as

one of the finest things Brian has ever done…the totally orchestrated cacophony was an innovation in rock when they used it in Smiley Smile, and is still done here better than anywhere else.

20/20 is, in summary,

a good album, flawed mainly by a lack of direction…more a collection than a whole.

How many other outmoded pop entertainers were likewise releasing flawed, directionless albums in 1969? But how many of them had a wealth of unreleased material to call upon that bettered all of their released work so far?

[2] Why is Murry Wilson collaborating with Brian Wilson in 1969? Maybe it’s the Wilson family closing ranks. In order to ‘protect’ Brian…

What might he need protecting from? His social life – and his access to drugs – doesn’t seem to have been curtailed; but his previously-unlimited access to recording studios has been mostly reduced to a room in his own home – and at a time when pop music and the ‘rock revolution’, dominating the LA music scene, was expanding outwards to dominate the world.

How many potential musical collaborators (with the catalytic capabilities of a Van Dyke Parks) might Brian Wilson have met if he were still in the working environment all his previous recordings were created within up to June 1967?

Was Brian Wilson’s father really the best co-writer then available?

[3] Brian Wilson said he should ‘be honest with the fans and I don’t see why I should lie and say everything is rosy when it’s not‘; this is at odds with every band whitewash since. The Beach Boys were probably unhappy (and understandably so) that Brian was so ‘honest’. This certainly scuppered their Deutsche Grammophon record contract – it’s difficult to make money out of a loss-making enterprise. More of this ‘honesty’ could have ended The Beach Boys. And then what would Brian have done?

[4] Celebrated UK DJ Jimmy Savile is currently much more renowned for his predilection for underage girls – at time of writing, a two years after his death, he remains ‘Britain’s worst-ever paedophile’. Francis Rossi of Status Quo (who collaborated with The Beach Boys in the 90s) recounted in a promotional interview how Jimmy Savile invited me to ‘sex party’ in his dressing room. Same day, elsewhere, Rossi Cringes At His Past Behaviour:

The Whatever You Want hitmaker found [a new Quo documentary] film, titled Hello Quo, impossible to view and confesses he would like to knock some sense into his cocky younger self.

Rossi, admirably, told Savile to “get out of it” when he suggested The Quo “come and see me tarts…there’s going to be something…some f***ing tarts we’ve got in”. And, in his response to his cocky younger self, Rossi appears to have learned yet more lessons about social etiquette since.

Age, experience, the passing of time, it generally brings ‘wisdom’, of a kind – even if it’s just an embarressment about one’s younger self.

[5] Dunno if Mike ever finished his ‘song about the planets’.

There is more to say about Transcendental Meditation, and Mike’s own application of it to himself. The NME guy obviously felt that Mike Love had a lot to say then.

In many ways, Mike Love could be seen as TM’s worst advocate ever. His insincerity, his bitterness, his legal proclivities, and an ongoing-acrimony with his family/friends/bandmates…these do not appear to be actions of an ‘enlightened’ being. However, in his continued success, as Mike Love of The Beach Boys, whatever hidden powers he is calling upon, they’re still working their magic.

All power to him.

[6] One could speculate that, without a $250,000 advance from Reprise/Warner Brothers (or even a far smaller advance from a smaller company), the Beach Boys might have actually declared bankruptcy, and ceased trading. Of course this, historically, is rarely the end for members of pop groups broken up by circumstance.

The Beach Boys had existed for nearly 9 years when their contract was signed with Reprise, with over 20 albums released by Capitol with their names attached.

How many solo artists, writers or performers could a disbanded Beach Boys have yielded in 1969? Brian obviously. Dennis. Bruce. Carl, even just as a session vocalist. Maybe the same for Al; or maybe back to dentistry.

Mike?

[7] A World Of Peace Must Come was missing for years, ‘then one day in the late ’80s the tape was rediscovered’; ‘twenty long years and a dozen deadend deals later’, it was finally released by Light In The Attic in 2008.